When Georgia Tomaras of Duke University Medical Center opened this year’s HIV Vaccines Keystone symposium last night, she said this is the first ever HIV Vaccines meeting that is held jointly with a meeting on B cell development and function. Given the many new antibody-related advances the field has seen in recent years, this is not exactly surprising. “We now have an increasingly detailed map of the vulnerable sites on HIV Envelope, due to an array of newly discovered broadly neutralizing antibodies and the identification of their targets,” said Tomaras, who is the co-organizer of the HIV Vaccines track of the conference. “Research focused on basic B cell biology is the foundation for the development of an HIV vaccine designed to drive the B cell arm of the immune response.”

Blog

As a rule, scientific subcommittee meetings aren’t the sort of things people—even certifiable geeks—flock to unless they’re looking for a quick snooze on a workday afternoon. The US National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) AIDS Vaccine Research Subcommittee (AVRS) meeting, however, appears to be an exception.

Check out our latest issue of VAX, which features articles on gene therapy research, results of a therapeutic vaccine trial and our most recent Primer.

Check out our latest issue of VAX, which features articles on gene therapy research, results of a therapeutic vaccine trial and our most recent Primer.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become so efficient that it leaves HIV-infected people with undetectable viral loads, allowing them to lead almost normal lives. Their lifespan, however, is still about ten years shorter than that of uninfected people. One major reason for this is that they suffer from chronic inflammation, much of it due to poor gut health, which can result in the translocation of bacteria into the blood.

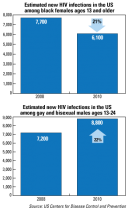

The good news: The number of new HIV infections among black females ages 13 and older declined 21% from 2008 to 2010.

Our latest edition spotlights the work of labs owned by Product Development Partnerships, the science behind particle-based recombinant vaccines and recent strides in AIDS vaccine research using humanized mouse models. Enjoy!

It’s been about a year since US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, whose department oversees the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), set a goal of achieving an AIDS-free generation (see VAX Global News,With HIV Incidence Plateauing, a Push for an AIDS-Free Society, Nov. 2011).

Hurricane Sandy got in the way! IAVI's offices in lower Manhattan were flooded during the horrific October storm--just as IAVI Report was going to press--so it took us a bit longer to get out the door. But we're finally here! Our latest edition of IAVI Report covers a brewing debate over how soon HIV-infected people should be offered treatment, highlights from the 2012 AIDS Vaccine meeting in Boston and a Q&A with US Military HIV Research Director Nelson Michael.

My report from a recent symposium on HIV cure research called “Towards an HIV Cure” ahead of the International AIDS Conference in Washington DC is now online. It discusses recent progress, but also challenges towards achieving a cure from HIV infection.

A major impediment in trying to develop vaccine candidates that can induce potent and broadly neutralizing antibodies is time. While all antibodies mature to some degree, the bNAbs uncovered from HIV-infected individuals in the chronic stages of disease take much longer to develop and follow much more convoluted developmental pathways. It takes several years of continuous stimulation by the infecting virus to drive mutations or changes in the bNAbs so that they can bind tightly to their targets, a process scientists refer to as affinity maturation (see VAX Jan. 2011 Primer on Understanding Advances in the Search for Antibodies against HIV). These bNAbs also typically have a long heavy chain complementary determining region 3 (HCDR3) that allow the antibodies to bind more strongly and to target more epitopes on the surface of HIV.

Until recently, many scientists were convinced that antibodies capable of preventing HIV infection could not be elicited through vaccination. But the discovery of dozens of potent broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) and the elucidation of some of their structural targets on HIV’s surface protein—the Envelope glycoprotein trimer that all bNAbs target—have revealed weaknesses that researchers believe can be exploited for both drug and vaccine development.

Scientists still do not know how the prime-boost regimen used in the R144 trial worked, but an ongoing analysis of nearly 1,000 genetic sequences from 110 HIV-infected recipients across the vaccine and placebo arms of the trial strengthen the theory that the candidate is applying selective pressure against a vulnerable region of HIV’s Envelope protein known as the V1/V2 region.

It’s been almost three years to the day that the surprisingly upbeat results from the RV144 trial in Thailand, which demonstrated the first and thus far only evidence of vaccine-induced protection, hit the newsstands and airwaves and re-energized the field. Yet a series of ambitious efforts set forth not long after to try and improve upon the modest 31.2% efficacy seen in the trial of 16,000 at-risk men and women from Thailand—and perhaps see a candidate to market—have been tempered by the realities of the ground war.

Check out my recent interview with Laura Guay, vice president of research at the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, that appears in VAX and focuses on recent findings from a breast milk study and the American Academy of Pediatrics' change in stance on infant circumcision.

You can find my recent package of stories about the AIDS 2012 conference on the new VAX website,www.vaxreport.org. The main story is about the evolution in HIV combination prevention strategies, while a second story deals with vaccine and microbicide updates from the IAS meeting.

Before HIV can enter a cell, the so-called Envelope spike on the viral surface needs to bind receptors on the target cell. This binding, researchers believe, causes the spike to open up and expose a normally hidden, inner portion of Envelope called gp41 that drives fusion of the viral membrane with that of the target cell, allowing the virus to enter. The structure of this opened “pre-fusion” state of the Env spike is unknown, but of great interest to researchers because it could inform the development of vaccine immunogens that induce antibodies that prevent the subsequent fusion of the membranes.

A research team led by Bing Chen, a structural biologist at Harvard Medical School, has created a lab-made version of the HIV Envelope trimer—from which the spikes on the outer surface of the virus are made—that is similar to the naturally occurring trimer. It is also more stable and more homogenous than previous lab-made versions, perhaps enough so that it could be used as an immunogen in a candidate vaccine for evaluation in human trials (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 12111, 2012). “I think we have made a truly stable and homogeneous Envelope trimer preparation,” Chen says, adding that this is the first time this has been achieved.

Just before this year’s International AIDS Conference (IAC) kicked off on July 22 in Washington DC, scientists met here on July 20 and 21 for a symposium called “Towards an HIV Cure” to discuss recent advances in HIV cure research, previewing many related research announcements that were later also discussed at the main conference. (The talks were under embargo until discussed at the main conference, which is why I am only posting this now.)

Last year, a groundbreaking international trial known as HPTN052 drew worldwide attention when it found that earlier ARV treatment of HIV-infected individuals led to a dramatic 96% decrease in HIV transmission to the uninfected partners in serodiscordant relationships (see VAX July 2011 Spotlight, An Antiretroviral Renaissance). The study also found that earlier treatment delayed the time to AIDS-defining events and tuberculosis and significantly decreased the incidence of clinical events for those with HIV.