Blog

A mixed picture: Latest trends in the US epidemic

News from the frontlines of the US AIDS epidemic, now more than three decades old, paints a mixed picture of national efforts to combat HIV transmission.

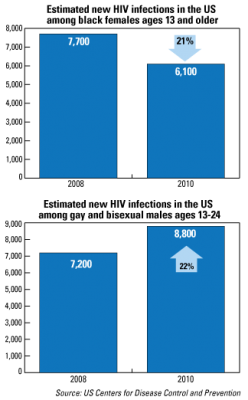

The good news: The number of new HIV infections among black females ages 13 and older declined 21% from 2008 to 2010.

The good news: The number of new HIV infections among black females ages 13 and older declined 21% from 2008 to 2010.

The bad: New HIV infections among gay and bisexual males ages 13-24 rose by 22% over the same period (see chart).

Researchers at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), who issued the report (Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010) described these findings as statistically significant. But they noted that additional annual estimates will be needed to substantiate the short-term trends they identified.

While the analysis is a decent snapshot of the US epidemic, it does not provide a state-by-state analysis. This makes it difficult to discern whether trends detected in certain high-risk populations were the result of dramatic changes in a specific region of the country, such as Washington, DC, the epicenter of the US epidemic, (seeWhy is HIV Ravaging DC, IAVI Report, Nov.-Dec. 2010), or whether they’re occurring nationwide.

The CDC analysis did not provide any explanations for the shifting trends. Researchers say they aren’t entirely sure why transmission—driven largely in both high-risk groups by unprotected sex—is going down among black women but rising at nearly the same rate among young gay and bisexual men. As such, the mixed findings raise compelling questions as to which HIV prevention strategies are working in key populations, and which may not be quite as effective.

In recent years, an array of federally funded projects and programs have targeted gay and bisexual men in San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, and other urban enclaves with large populations of men who have sex with men (MSM). This includes efforts like the Act Against AIDS Campaigns launched in 2009 by the CDC to deliver important HIV prevention messages to gay and bisexual men (as well as other vulnerable groups), to combat growing complacency about the risk of contracting HIV.

It is unclear how effective these efforts have been in some communities. Young black MSM now account for more new infections than any other subgroup by race/ethnicity, age, and sex. The CDC notes that there was a 12% increase in HIV incidence among MSM overall from 2008 (26,700 reported cases) to 2010 (29,800 reported cases).

Local communities with high HIV incidence are also testing various strategies to reach high-risk communities. In Washington, DC, where HIV prevalence has been compared to that of some developing countries, HIV tests tripled from 43,000 in 2007 to 122,000 in 2011. The district distributed five million male and female condoms in 2011—a 10-fold increase from 2007—and provided free sexually transmitted disease testing to 4,300 adolescents in 2011.

The Kaiser Family Foundation reported last year that new HIV infections in the district were down slightly in 2010 compared to 2009. The most significant declines among adults were found among injection drug users, and were likely due to syringe exchange programs.

Epidemiologists point out that while the decline in new infections among black women is encouraging, HIV is still an overwhelming presence. Black women accounted for 13% of all new HIV infections in the US in 2010, and 64% of new infections among women. “It is important to realize that African American women are still one of the populations most affected by HIV,” says Donna Hubbard McCree, associate director for health equity at the CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. “They are still becoming infected at 20 times the rate of Caucasian women.

Jennifer Kates, vice president and director of Global Health & HIV Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, says the CDC began to recently notice that incidence among black women was declining. The three years of data included in the current analysis confirms that trend. Still, she says, without state or regional data, it is difficult to decipher what might be driving the national numbers.

While the analysis is a decent snapshot of the US epidemic, it does not provide a state-by-state analysis. This makes it difficult to discern whether trends detected in certain high-risk populations were the result of dramatic changes in a specific region of the country, such as Washington, DC, the epicenter of the US epidemic, (seeWhy is HIV Ravaging DC, IAVI Report, Nov.-Dec. 2010), or whether they’re occurring nationwide.

The CDC analysis did not provide any explanations for the shifting trends. Researchers say they aren’t entirely sure why transmission—driven largely in both high-risk groups by unprotected sex—is going down among black women but rising at nearly the same rate among young gay and bisexual men. As such, the mixed findings raise compelling questions as to which HIV prevention strategies are working in key populations, and which may not be quite as effective.

In recent years, an array of federally funded projects and programs have targeted gay and bisexual men in San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, and other urban enclaves with large populations of men who have sex with men (MSM). This includes efforts like the Act Against AIDS Campaigns launched in 2009 by the CDC to deliver important HIV prevention messages to gay and bisexual men (as well as other vulnerable groups), to combat growing complacency about the risk of contracting HIV.

It is unclear how effective these efforts have been in some communities. Young black MSM now account for more new infections than any other subgroup by race/ethnicity, age, and sex. The CDC notes that there was a 12% increase in HIV incidence among MSM overall from 2008 (26,700 reported cases) to 2010 (29,800 reported cases).

Local communities with high HIV incidence are also testing various strategies to reach high-risk communities. In Washington, DC, where HIV prevalence has been compared to that of some developing countries, HIV tests tripled from 43,000 in 2007 to 122,000 in 2011. The district distributed five million male and female condoms in 2011—a 10-fold increase from 2007—and provided free sexually transmitted disease testing to 4,300 adolescents in 2011.

The Kaiser Family Foundation reported last year that new HIV infections in the district were down slightly in 2010 compared to 2009. The most significant declines among adults were found among injection drug users, and were likely due to syringe exchange programs.

Epidemiologists point out that while the decline in new infections among black women is encouraging, HIV is still an overwhelming presence. Black women accounted for 13% of all new HIV infections in the US in 2010, and 64% of new infections among women. “It is important to realize that African American women are still one of the populations most affected by HIV,” says Donna Hubbard McCree, associate director for health equity at the CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. “They are still becoming infected at 20 times the rate of Caucasian women.

Jennifer Kates, vice president and director of Global Health & HIV Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, says the CDC began to recently notice that incidence among black women was declining. The three years of data included in the current analysis confirms that trend. Still, she says, without state or regional data, it is difficult to decipher what might be driving the national numbers.

Kates says multiple factors are likely contributing to the increase in incidence among gay and bisexual young men. HIV prevalence among the group is already high, which substantially raises the risk of acquiring HIV. Discrimination against MSM and a sense of diminished risk, especially among younger gay men who were born well after the epidemic began, could also be fueling the rising incidence.

Young gay and bisexual men may also lack access to health care, or be unaware of their risk of acquiring HIV, says Hubbard McCree. Stigma may also discourage high-risk individuals from being tested. “All these issues are interrelated,” she says.

Hubbard McCree says that in recent years the CDC has been trying to implement the most cost-effective and scalable interventions in regions and populations most heavily affected by HIV, an approach the CDC refers to as high-impact prevention.

Ken Mayer, medical research director and co-chairman of the Fenway Institute in Boston, which conducts health research and advocates for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered communities, says national resources need to be “proportionate” to the impact on various communities. “The new numbers are concerning,” he says, referring specifically to the rise in incidence among young MSM. “The federal government has to increase resources for culturally competent testing, linkage and prevention programs for MSM.”

Mayer says the programs need to recognize that there are “multiple micro-epidemics” among MSM in the US. “Innovative programs need to be tailored for black and Latino MSM, as well as younger MSM. One size will not fit all.”

Hubbard McCree says that in recent years the CDC has been trying to implement the most cost-effective and scalable interventions in regions and populations most heavily affected by HIV, an approach the CDC refers to as high-impact prevention.

Ken Mayer, medical research director and co-chairman of the Fenway Institute in Boston, which conducts health research and advocates for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered communities, says national resources need to be “proportionate” to the impact on various communities. “The new numbers are concerning,” he says, referring specifically to the rise in incidence among young MSM. “The federal government has to increase resources for culturally competent testing, linkage and prevention programs for MSM.”

Mayer says the programs need to recognize that there are “multiple micro-epidemics” among MSM in the US. “Innovative programs need to be tailored for black and Latino MSM, as well as younger MSM. One size will not fit all.”